Mera Rubell, co-founder (with Don Rubell) of Rubell Family Collection is joined by collection director, Juan Valadez in commenting on artist Purvis Young's series of Pregnant Women and Protesters in the current exhibition – through June 22, 2019. www.rfc.museum 95 NW 29 St. Miami, FL 305-573-6090

Purvis Young exhibition a “Goodbye” to Wynwood for Rubell Family Collection

Riding his bicycle around Overtown’s trash-strewn streets in the 1970s, Purvis Young didn’t cut a dashing figure. Brawny, but disheveled – shirtsleeves torn off – rough-spoken. He might be dismissed as another lost soul. Instead, Young was a keen observer and eloquent griot, using cast-off materials to create a vast, gritty visual documentation of his stomping grounds and the mortal struggles he and his neighbors endured.

Young died in 2010, but his paintings are having an enduring “moment” in Miami and abroad. His work currently is featured in a satellite show of the Venice Biennale and in prominent commercial gallery exhibits. Besides numerous Miami institutions, a growing list of other prestigious arts venues have acquired his work. A momentous presentation can be seen locally – through June 22 – at the Rubell Family Collection. Along with work by scores of other celebrated artists, Mera and Don Rubell, and their son, Jason, maintain the largest assemblage of Young’s copious production.

Once a vibrant haven of African-American theater and music, Overtown was bisected in the 1960s by the construction of Interstate 95, propelling its decline. Young, born in 1943, found few opportunities besides getting in trouble. But as an incarcerated teenager, he discovered an aptitude for drawing. Following his release from prison for breaking and entering, he befriended two administrators of the Miami-Dade Public Library’s art program, Barbara Young (no relation) and Margarita Cano. Recognizing Young’s prodigious talent, they gathered art books for him to peruse, which he did avidly. They provided art supplies and coordinated Young’s painting landmark murals on the library system’s Culmer Overtown branch. Young identified with Goya, Van Gogh, Rembrandt and El Greco’s tackling of war, poverty and class bias.

In the early ’70s, Young's artwork, painted on discarded plywood, metal trays, cardboard and other detritus, protested the Vietnam war, whose beleaguered veterans languished around him. But he also celebrated exuberant street life. He affixed his artworks onto abandoned storefronts and crumbling walls along Overtown’s “Goodbread Alley.” Others he gave away or sold to passersby – individually and by the trunk load.

Artist César Trasobares facilitated a commission for the Northside Metrorail station and included Young in exhibitions he curated. Collector Bernard Davis also presented Young’s work to a wide audience. But for decades, Young’s career consisted of haphazard sales and problematic arrangements with “managers,” some of whom exploited him.

Then, in 1999 mutual friends, dealer Tamara Hendershot and Jeffrey Knapp, introduced Young to the Rubells in his overflowing warehouse studio.

“We knew we were in the presence of real talent,” Mera Rubell recently said. Learning that his decades-long production – some 3,000 paintings – might be lost due to a threatened eviction, the Rubells stepped forward. “It was a treasury that had to be preserved,” she said. The collectors contracted to purchase Young’s entire stock – through monthly installments over five years. They also committed to donate work to worthy institutions (like the 109 pieces installed in Morehouse College’s chapel in Atlanta).

Juan Valadez, now RFC director, was a new hire when he and a small team took charge of five truckloads of dirty, splintery, but artistically compelling figurative works – registering, measuring, photographing, describing and painstakingly cleaning them. “They received the same treatment as if they were Picassos,” Mera Rubell asserts.

The current solo show marks the RFC’s imminent departure to an expanded Allapattah facility. Valadez has staged this “goodbye” exhibition not as a winsome pastiche of colorful, readily accessible imagery, but as a forthright, dignified presentation of Young’s most compelling, poignant and difficult material.

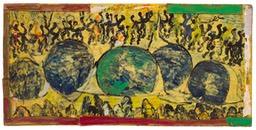

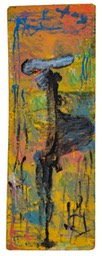

Roughly 100 mixed-media paintings are organized into 14 themes – from birth to death and beyond. Throughout, Young’s wiggly, calligraphic drawing, expressionistic smears and textured brushstrokes are signature elements in rendering favored motifs: writhing figures, muscular horses, elongated faces, trucks, bugs, buildings, boats, coffins, syringes, angels. His rough-hewn masterworks wail in protest to intractable social disasters, including the 1980 McDuffie riots. Voluptuous figures of very pregnant women – whose bulges press against the paintings’ frames – occupy the first large room. Pregnancy represents the future. “They giving birth to a new nation,” Young says in the catalog. But they also embody vulnerability and abandonment.

Young’s depictions of murder – mostly single prone figures surrounded by mourners and protesters – are vivid and heartbreaking. Looming syringes – sometimes borne overhead like coffins – vividly rail against the drug plague.

Fragile watercraft, surrounded by sharks, carry desperate Haitians and Cubans, but also Vietnamese boat people. Arms are raised in protest and prayer. Young frequently said that his horses symbolize freedom – a precious commodity.

Whatever his innate talent, Young improved through unceasing practice. He used paint he found or that neighbors gave him. Local firefighters donated leftovers of the yellow they used to paint hydrants.

“What he painted on came from the conditions he was representing,” said Valadez. “Moreover, the people he was representing were cast off and dismissed by society’s institutionalized racism. So, the material was forlorn and dismissed and disregarded, as were the people that he would represent on them. But when he’s doing it, he’s elevating both the material and the people to an extremely high level.”

Young used frames to great effect: “He loved to embellish the painting with framing, and often the framing became part of the painting,” said Mera Rubell. “But he would then paint over the frame or incorporate the frame into the painting.”

Asked if Young’s uniquely expressive “Faces” (some came to him in dreams) were influenced by Byzantine icons, Valadez replied, “He has seen it all, really! COBRA artists and everyone. And it’s not just Rembrandt; it was Surrealism, it was Franz Marc, Kirchner; he had seen Asian work. …”

Those influences were thoroughly digested. Young’s art is uniquely his own.

Poverty and injustice remain undiminished since his death nine years ago. His paintings remain to challenge us. Mera Rubell makes clear: “When you're dealing with great artists, their work is always relevant, and when you're dealing with great, great artists, their work is relevant for centuries.”