JAMES PROSEK’S NATURAL CURIOSITY IS ON VIEW AT THE LOWE ART MUSEUM

In selecting artist James Prosek for a major exhibition, Lowe Art Museum director Jill Deupi reached back to her days at the Fairfield University Art Museum in Connecticut, where she first met and exhibited (in 2011) the young but accomplished artist and writer, who lived nearby. While a quick scan of his wildlife-themed paintings suggests a straightforward celebration of nature through masterful realism, there’s lots more going on here.

As Deupi notes during a gallery tour, “There are multiple points of entry, and it’s up to the viewer to decide how to engage.” If one chooses to look deeper than the pleasures of seeing majestic animals, exquisitely portrayed, there’s the level of Prosek’s messaging about our relationship to the natural world and how we seek to tame it — literally with dams, canals and fences and figuratively with our naming systems.

Some of his imagery derives from the documentary traditions of 18th century explorer-naturalist-illustrator-collectors who also promulgated the Linnaean taxonomy (class, order, family, genus, species, etc.), an attempt to impose order upon the bewildering chaos of nature. Prosek’s life-size fish from the Florida-Atlantic region, painted on tea-stained paper, dramatically showcase his mastery of this European tradition of representation, as well as those of India and China. Prosek is a hardcore observer. Each highly nuanced principal subject is accompanied by detailed, annotated field sketches of plants and crustaceans that share its habitat.

He actually witnessed his “Atlantic Great White Shark” being captured near Cape Cod. Fascinated by the dramatic shifts of sheen and coloration that telegraphed the animal’s visceral reaction to peril, the artist managed to portray its variegated skin tones in a combination of materials that include watercolor, gouache, colored pencil, graphite and iridescent mica powder. Rendered in its daunting 12-foot length, open-mouthed and equipped with razor-sharp teeth, this predator appears formidable and menacing, but paradoxically, its flattened presentation suggests a mounted specimen rather than a struggling captive.

An array of black silhouettes of Everglades flora and fauna, like those found in a field guide — except life-size — runs the length of the gallery, forming an impressive mural. While Prosek was in town creating this commissioned feature — with assistance from Lowe staffers — Deupi eagerly introduced him to a family of macaws that performs raucous daily flyovers along South Dixie Highway. Native to the tropical rainforests of South America, these birds likely escaped captivity during Hurricane Andrew. As Deupi puts it, “the result of ruthless nature intervening with man’s intervention.” Now residing in the area, they became inspirations for Prosek.

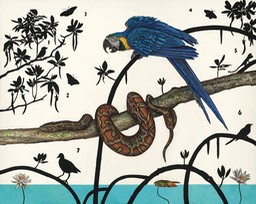

His Audubon-worthy, watercolor of a blue-and-yellow macaw includes a red mangrove branch and a morning glory flower. Prosek reprises the macaw for a larger painting, where he adds a similarly realistic Burmese python, but again juxtaposes black silhouetted butterflies, birds, plants and numerals. The mix of stylistic representations introduces an unsettling conceptual twist, contributing to what makes Prosek a contemporary artist.

James Prosek’s “Paradise Lost 1 (Burmese Python and Blue and Yellow Macaw, Everglades)” is on view through Sept. 8 at the Lowe Art Museum in Coral Gables. Image courtesy Prosek and the museum.

Other nonnative species also contribute to the conceptual intrigue. “A Tyger for William Blake” depicts a tiger and a leopard, locked in an intimate tangle. Are they fighting or engaged in foreplay that could result in a hybrid creature adapted to the warmer, wetter Florida of the future? Like Blake, the Romantic-era artist-mystic poet, Prosek seems to question the design and origins of life. “The reason we included these works,” Deupi says, “even though it’s not the Everglades, is because it’s the logical extension of what’s happening now if you can have lionfish and Burmese pythons.”

Inspired by his childhood exposure to Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History and its famous dioramas (combining painted backgrounds with rocks, trees and taxidermy specimens), this old-school format is Prosek’s latest undertaking. “Paradise Lost 2,” created this year, features a meticulously painted Everglades background with a section of ash tree in the foreground, supporting a trompe-l’oeil ceramic ghost orchid. It’s an uncanny tour-de-force tribute.

Prosek isn’t a loud proponent of environmental causes, but the World Trout Initiative he co-founded has raised millions of dollars for cold-water habitat conservation, and his work clearly seeks to deepen audiences’ appreciation of the world we share. Moreover, as the Lowe’s communications specialist Bridget O’Brien suggests, “Some of his ideas about invasive species have correlation to the conversations we’re having about human migration.”

Deupi readily connects two other exhibitions the museum is hosting, whose themes are equally topical and provocative.

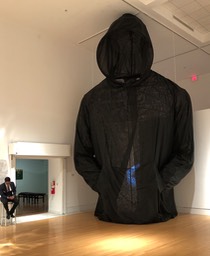

Billie Grace Lynn’s “Hoodie” is on view through Sept. 15. Image courtesy Lynn and the museum.

“A House Divided” is the latest of artist and University of Miami instructor Billie Grace Lynn’s probing explorations of social conflict. Using her students as subjects, models and informants, she has created a multilayered, audience-participatory project that addresses the raw issues of race-based inequality, discrimination and disrespect. It comprises an online forum; a three-hour video of intimate testimonials; a teetering reflective obelisk; and an adjacent, 22-foot-tall, hollow, veil-like “hoodie” sculpture, suspended from the ceiling, that visitors can enter for another kind of reflection.

“Visions of Place: Complex Geographies in Contemporary Israeli Art” was curated by Martin Rosenberg from Rutgers and J. Susan Isaacs from Towson University. The exhibition presents work by 33 artists from Israel’s Jewish, Muslim and Christian communities. Some express despairing or angry visions, but there’s captivating beauty and humor, as well — effective when dealing with sensitive topics. Tamir Zadok, for example, has set up a rack of travel postcards, showing the Eiffel Tower, Colosseum, etc. But effecting an adroit spin on the pejorative expression “wandering Jew,” he created “Wonder Jew” by superimposing images of himself proudly wearing his Israeli Army uniform in front of these iconic backgrounds.

“James Prosek: Contra Naturam/Against Nature” is on view through Sept. 8. “Visions of Place: Complex Geographies in Contemporary Israeli Art” is on view through Aug. 4. Billie Grace Lynn: A House Divided” is on view through Sept. 15 at the Lowe Art Museum, 1301 Stanford Drive, in Coral Gables. Hours are 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday and noon-4 p.m. Sunday. Admission is $12.50, $8 for seniors and non-University of Miami students, and free to Lowe members, UM students, faculty and staff, children under 12 and veterans with proper ID. Call 305-284-3535 or go to LoweMuseum.org. Listen to audio from Jill Deupi.

Top photo: James Prosek’s “Atlantic Great White Shark” courtesy the artist and the Lowe Art Museum.

ArtburstMiami.com is a nonprofit source of theater, dance, music and performing-arts news. Sign up for our weekly newsletter and never miss a story.