Coral Gables Museum exhibits brings the outdoors inside

BY GEORGE FISHMAN

George@WordHarmony.com

On first appraisal, Philip Johnson’s Glass House and Hilario Candela’s Miami Marine Stadium seem to have little in common.

The Glass House was conceived and created in 1949, during a mid-career break, by America’s “dean of architecture,” the scion of a New Amsterdam family. A pristine box surrounded by a dozen other Johnson-designed structures, it nestles amid forested hills outside New York City and was a weekend getaway for Johnson and his friends.

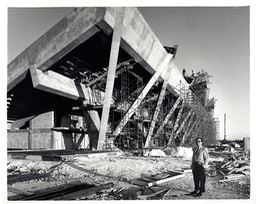

The 1963 stadium, designed to seat more than 6,000, perches at the edge of a water-filled basin. Its Cuban-born architect, then 28 and freshly settled in the United States, developed the innovative cast concrete grandstand structure for speed boat races.

The Glass House received National Historical Landmark designation during Johnson’s lifetime and remains a treasured site for scholarly pilgrimage. The stadium, essentially abandoned by Miami administrators in 1992, became a “canvas” for graffiti artists. It barely escaped demolition.

Now the two buildings share protected status, and the stadium’s supporters are campaigning for renovation funds. Complementary exhibitions at the Coral Gables Museum focus on the two structures, telling compelling stories — in video, sculpture, image and text — about architecture, South Florida design and the engagement of man-made structures with nature.

According to director Christine Rupp, the museum’s mission is to celebrate the civic arts — and not just in Coral Gables: “We explore and celebrate architecture, urban planning, sustainable development and preservation.”

The exhibitions deliver.

In A Chapel in a Cathedral of Nature, architectural and interior design photographer Robin Hill reveals the outer and inner character of The Glass House through a series of arresting color photographs, taken during four seasons and at various times of day — and from a multitude of vantage points. Juxtaposed against the porous limestone gallery walls, the architectural and natural themes emerge vividly.

Johnson scholar Hilary Lewis, the architect’s junior by several decades, co-wrote with him and lectures internationally. Her texts further reveal the site, the 13 buildings and the man.

“As a work in progress for over 40 years, the project serves as an autobiography of Johnson’s interests and as a place to experiment,” she said in an interview.

These diverse structures and their placement reflect Johnson’s affection for 18th century European landscape design. “But what we don’t expect is to see modern architecture placed within that,” according to Lewis. “We normally expect grottos, gazebos and temples.”

What we do see is nature reflected in the architecture. According to Hill, “The signature photograph of this exhibition is Glass House Dawn. Photographed in pre-dawn light at the height of the fall season and with all the lights on, I was able to capture something unique by placing my camera almost on top of the water in the swimming pool, thereby creating a full reflection of the Glass House.”

It’s a majestic image, in which the photographer pays homage to the architect while also expressing his own vision. “I try to fuse together the inherent beauty of the architecture I’m photographing with my own visual philosophy, which places weight on the interaction of light and shadow and the effect that has on geometry, materials and the perception of space, ” he said.

Artist Rirkrit Tiravanija’s child-size model of the Glass House helps to create an “immersion experience.” Developer and collector Craig Robins loaned it to the exhibition.

Visitors can enter the building and look out two sides into the “expensive wallpaper,” as Johnson referred to his enveloping landscape. In the exhibition, mural-sized photos of the wooded hillside and pavilions serve this theatrical function, reflecting Tiravanija’s and Robins’ commitment to the convergence of education, community, art and architecture.

Initially, says Rupp, staff saw the two exhibits as separate, distinct entities: “a small home, a large stadium; a preserved venue, another fighting to be saved.’’ But as the exhibits evolved, connections between them became more evident. “Both continue to inspire artistic works; both intrinsically involve the natural environment; both are iconic structures.”

Miami’s indoor-outdoor architecture continues to draw inspiration from both buildings, notes Lewis, and as Rupp summarizes, both buildings use their settings, the open environment, to complete and complement their design.

For Rosa Lowinger, a Cuban-born art and architecture conservator, the role of guest curator for the Marine Stadium exhibition is personal. As a child she watched speedboat races from her parents’ boat. She has written the definitive book on the stadium’s architectural progenitor, Havana’s Tropicana Club, designed by Candela’s mentor, Max Borges.

For Concrete Paradise, Lowinger has gathered lively resources from its heyday; still, she does not disparage the creative activities of graffiti artists and Parkour sport adventurers during recent years. Lowinger is convinced that their embrace has helped save the stadium’s life.

“It’s nice to talk about the past, but if you look now … there are photo shoots, graffiti artists, skateboarders; it has a contemporary hip-hop, street-art layer on top of the historic foundation.”

This creative energy has provided currency to the conversation about renewing the stadium’s life. Preservation was not assured, and Candela feared losing his “child” until support reached a critical mass. This included Gloria Estefan’s public embrace of the project, which its “Friends” organization had been promoting since 2008 and that now is bolstered by the city and county mayors and the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Lowinger’s enthusiasm is evident as she proclaims – and aims to demonstrate – “how this is the one building, because of its past and its present, is completely synonymous with Miami.”

And the exhibition? “It’s the cherry on top of the sundae. I get not only to preserve it, but to make the case for it.”

Concrete Paradise will serve as an introduction for newcomers, while long-time South Florida residents will find memories of Easter-morning services, ear-splitting boat races, boxing matches, fireworks and concerts by jazz, classical and pop music royalty. At the brink of launch into a new life, the stadium deserves an affectionate spotlight, and this pair of exhibitions at the Coral Gables Museum is equally illuminating for mind and heart.

If you go

What: The Glass House: "A Chapel in a Cathedral of Nature"

When: Through Oct. 20

What: The Miami Marine Stadium: “Concrete Paradise”

When: Oct. 17 to Jan. 5, 2014; Open Tuesday-Sunday; hours vary

Where: Both at Coral Gables Museum, 285 Aragon Ave., Coral Gables

Information: http://coralgablesmuseum.org; 305-603-8067