Debra and Dennis Scholl speak about forming a collection of Aboriginal Australian art, which they share through the exhibition, "No Boundaries." Curator María Elena Ortiz talks with artist Firelei Báez about her show, "Bloodlines" – both at the Pérez Art Museum Miami

‘Bloodlines,’ ‘No Boundaries’ cross common paths at PAMM

By George Fishman

What happens if you’ve been collecting contemporary art for more than 30 years and find yourselves stymied by the increasing dominance of oversize personalities and money? For Debra and Dennis Scholl, it has meant looking to communities of Australian Aboriginal artists to replenish their passion for discovery, research, acquisition and sharing — without giving up entirely on collecting from other regions of the world.

A segment of their collection, specifically the paintings of nine tribal elders who all began painting late in life (and mostly died within the past decade), comprises a traveling exhibition, “No Boundaries,” currently on view at Pérez Art Museum Miami.

The land and community life of the Australian desert from which the “No Boundaries” artists draw their inspiration are far removed from South Florida, but culture’s core engagement traverses continents.

In a recent presentation at PAMM, curator and historian Henry Skerritt quoted colleague Ian McLean. “These paintings are aimed at the Western world with all the power and accuracy of a well-thrown spear.” Such is the universality of their messages, and their presence in the gallery is visceral, if not aggressive.

Meanwhile, physical proximity and history connect South Florida, the Caribbean and Latin America through family ties, food, performance and the visual arts. Yet political and cultural challenges remain, dramatized in the current expatriation conflict between the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

“Bloodlines,” Firelei Báez’s concurrent exhibition, plumbs the tangle of racial, sexual and cultural forces that affect and inform people of Caribbean origin. Associate curator María Elena Ortiz initiated the project; she also wrote a deeply researched essay for the accompanying bilingual catalog. It is introduced by new PAMM director Franklin Sirmans, whose 2014-15 “Prospect.3: Notes for Now” art fair in New Orleans explored some kindred themes.

Báez’s intrigue with heritage and history is as intimate as the color of her skin and the curl of her hair. Born in the D.R. to Dominican and Haitian parents, she was raised in the United States.

“My work is about bodies and histories and landscapes and all the stories we make up in order to present ourselves to others,” she said in a 2011 video for El Museo del Barrio in New York.

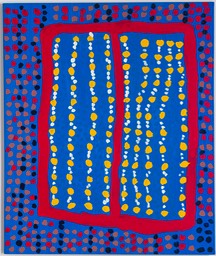

The Aboriginal paintings are also physically and conceptually multilayered. Tommy Mitchell’s Warlpapuka is a series named for a prominent mountain that has long supplied travelers with game and other foodstuffs. The artist explained to Edwina Circuitt, Warakurna Art Center manager, that besides an element of mapping landmarks, his paintings also reference the spotted coat of the crescent wallaby.

Creeks, tracks, trees and waterholes are disguised and revealed within skeins of multicolored dots, applied in layered rows and clusters. The complex ancestral creation narratives — referred to as Dreamtime — are interwoven in Mitchell’s tapestry-like compositions. Kinship relationships remain vital in the Aboriginal social interactions that govern tribal alliances and hereditary connections to the land.

Examining the work in “Bloodlines,” we find tension between the genetic heritage of slavery that’s part of most Caribbean people’s identity and the desire to conform to colonial European standards of beauty.

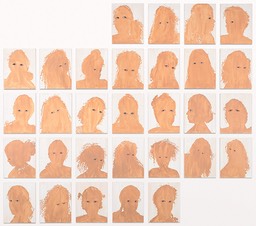

First seen as part of PAMM’s 2014 “Caribbean: Crossroads of the World” exhibition, Can I Pass? is a playful but arresting exploration of how racial bias — as judged by skin tone and hair curl — has been imposed upon and adopted by people of color. During June 2011, Báez created daily silhouette self-portraits, matching the skin tones to variations she observed on her own forearms due mostly to weather changes.

This analysis corresponds to the “brown paper bag test” of the American South. “It’s like an American standard for whiteness,” she said. “You had to match it or be lighter to pass.” Within the African-American community, the same test excluded darker people from fraternal organizations and other institutions. “Pigmentocracy” lingers, giving privilege to lighter-skinned people in various contexts.

Can I Pass? also represents the Caribbean “fan test,” whereby the stiffness and curl of a woman’s hair arbitrarily determined her race. A natural hygrometer, Báez’s hair responded to changes in humidity, producing textures ranging from the “ideal” soft wave of European hair to the “bad” kinkiness of African hair (which beauty salons are still called upon to temporarily overcome). All the while, Báez confronts the viewer with a steadfast gaze.

Female bodies — mostly buxom and curvy — are central to Báez’s work. Their “Rubenesque” shapes challenge European-American paradigms of slenderness, while highlighting the divergent ways figures are judged — even fetishized. Báez’s figures are ornamented with complex pottery and fabric patterns — evoking cultural intermingling; they’re covered with luxuriantly drawn fur or drenched with color. Fanciful hairdresses evoke the labor-intensive intricacy of “women’s work,” the exoticism of carnival, “native” costume and the crowns of European royalty.

The recurring silhouette format also serves as a liberating disguise. There’s also an empowering tone among Báez’s works.

“We always know certain communities for their suffering or their discrimination or their negative histories,” explained Ortiz.

Báez traces symbols and stories — a good luck charm or an item of clothing, like the tignon — through time and geography. She tells a nonlinear, multilayered history of Caribbean culture that demonstrates flexibility and agency among its people.

“A lot of times when I paint a portrait it’s not so much an individual, but how that individual is a repository for all these different histories,” Báez says. Along with her “native” feather headdress, Carnival dancer Anayansi, for example, reveals part of her heritage through the Chinese ink brush-style decoration on her legs. For Báez, painting skin “is more a kind of Rorschach for me; it’s a point of projection.”

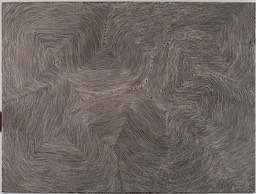

While no bodies or other pictorial contents are overtly represented in “No Boundaries,” body-painting is vital to the work of Midpul (aka Prince of Wales). A member of the Larrakia people from the shoreline region around the north-central city of Darwin, Prince danced and sang in initiation ceremonies — and even for Queen Elizabeth during her 1963 regional tour.

Within traditional ceremonies, he painted co-celebrants’ bodies, but following a stroke that limited his mobility, Prince found a new medium to continue his spiritual practice. Said Scholl, “He simply transposed how he would normally paint somebody’s torso … and put it on the canvas. It was a pattern that he was interested in, and instead of painting it on a person, like he had for many decades of his life, when he was offered canvas he simply took the authentic ritual painting that he would’ve made and put it on the canvas.”

That inventive strategy is emblematic of a powerful movement of contemporary abstraction, characterized by distinctive stylistic individuality. Many critics and collectors consider the best of contemporary Aboriginal art to be the equal of any work created today. Skerritt declared, “At their most literal level, these paintings ask us to be conscious of the presence of spirits and of ancestral beings. And in a much broader sense, they force us to acknowledge the presence of different ways of seeing and valuing the same world.”

The catalog’s essays explore the historical context of Aboriginal painting, the artists’ personal stories and their vital relevance in today’s cultural and physical climate.

While anchored in a tradition dating back 40,000 years in rock drawing, sand- and body-painting, Australian Aboriginal art was virtually unrecognized in the global art world until the 1970s. Previously, cultural artifacts were recorded and collected primarily by ethnographers and archeologists. But the seriousness of art-making was demonstrated to a white schoolteacher, Geoffrey Bardon, in 1971, when he offered modern painting materials to schoolchildren in the central desert community of Papunya. The elders were alarmed, insisting that only men initiated in their heritage were qualified to judiciously reveal its power and secrets, which they began to do, using acrylics and canvas.

Mapping the psychic and physical landscape is an attribute both of sand-painting and of painting on canvas. “You don’t see a lot of paintings in museum exhibitions that are placed on the ground, and we chose to do that in the exhibition, because the paintings were made on the ground,” Scholl said. “The artists were sitting down on the ground with the canvas in front of them. They would draw information, waterhole locations, topographical things in the sand, so the paintings on the ground are reflective of that idea.”

A side benefit: Children “can get down on their hands and knees where they spend most of their time and get their nose this far away from the painting,” he enthused.

While conveyed in distinctive regional and individual artistic styles, Aboriginal painting embodies a belief system in which past and present, natural and supernatural are superimposed. This worldview is integral to the physical and spiritual survival of people who have lived in an unforgiving environment for millennia but whose greatest challenges are those resulting from European colonization, beginning in the late 1700s.

Starting with the Papunya art movement, numerous regional art centers now facilitate Aboriginal art-making and marketing. Each of the artists in “No Boundaries” had established his stature as a spiritual leader before starting to paint, although some also worked for cattle ranchers, allowing them to remain on their ancestral lands. The linear patterning, arrays of dots, concentric and amoeba-like forms, linear meanders and complex “pointillist” color mixes reference ancestral mythology, while simultaneously constituting an independent abstraction. Their uncanny power is arresting, and they demand a slow, deliberative contemplation — not to “figure them out,” but to allow their quiet animating force to soak in.

As Scholl says, “There’s no way, leading a western lifestyle, that you’re going to be able to understand the deep spiritual meaning that surrounds these paintings — even if it was explained to you. Just appreciate the fact that there’s a deep, rich cultural bonanza, and you get to participate in some small fraction of it.”

Art sales currently fund critically needed medical and educational infrastructure in these remote parts of Australia. Additionally, Aboriginal artworks have galvanized reform movements aimed at restoring native land rights and redressing other grievances. The longstanding social injustices in Australia parallel slavery, land confiscation, indigenous “reservations” and other forms of discrimination in the Americas.

Báez’s work combines psychology, history, symbols and political satire in a rich fabric of folk traditions and sensual physicality. Her large, doorway-like painted construction, created specially for the PAMM exhibition, epitomizes the skewed passageway between Miami and its “backyard,” while also referencing Gordon Matta-Clark’s multilayered architectural “dissections” of buildings and histories.

The regional connections of “Bloodlines” and global reach of “No Boundaries” loosely summarize PAMM’s two-year programming history. Director Sirmans will do well to absorb their success in fashioning his own vision for the museum.