Frost Art Museum director Jordana Pomeroy and art scholar Kenneth Silver discuss the exhibition.

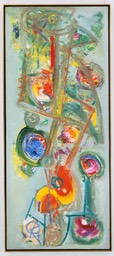

Works of Hans Hofmann on display at Frost Museum

george@QRartguide.com

Kenneth Silver, adjunct curator at Greenwich Connecticut’s Bruce Museum, recently addressed guests assembled at the Frost Art Museum to preview the exhibition he had organized. “That almost no one knew that Hans Hofmann had two major murals in Manhattan … isn’t it astonishing?” he asked.

The “birthing” of this unusual exhibition and the role of murals in Hans Hofmann’s illustrious career are both intriguing stories. Previously underappreciated, Hofmann’s mural projects presented a significant challenge to this already mature and celebrated artist and helped inspire his highly treasured later paintings — some of which round out the show.

Major mid-century New York critic Clement Greenberg wrote, “No one has digested Cubism more thoroughly than Hofmann, and perhaps no one has better conveyed its gist to others.” Scores of books and journal articles document Hofmann’s influence on the New York school of Abstract Expressionist and Color Field painters — through his teaching and his work. Among the leading artists who owe much to Hofmann: Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Franz Kline, Helen Frankenthaler, Larry Rivers and Mark Rothko. So, unheralded Hofmann murals are worth getting excited about — especially for an aficionado like Silver, who teaches modern art at New York University.

Several years ago, while the Bruce Museum had one of Hofmann’s late so-called “slab” paintings on loan, their registrar, Jack Coyle suggested the Hofmann Trust might support an innovative project. A visit to their Manhattan storage facility revealed studies for several New York murals. Silver was thrilled. “I was born in New York City; I was brought up in New York City; I live in New York City, and there are Hans Hofmann murals in New York City?” he exclaimed. “And they’re splendid murals,” he added. … “glass mosaic murals, which he [Hofmann] designed.” Within an hour, Silver and his trust colleagues had visited one mural in an office building on Third Avenue and another at a high school on West 49th Street.

Learning that little scholarship had been done concerning these works, Silver proposed a project. They would “introduce New Yorkers to something they didn’t know and examine this aspect of Hofmann’s art that nobody really talks about.” The exhibition’s trajectory would launch with Hofmann’s designs for a Peru project for which there are major studies, but that never came to fruition. Then it would introduce the various studies and photographs of the two New York murals that are realized. These, in turn, would set the stage for what Silver — and the art market — consider Hofmann’s artistic apotheosis: the slab paintings. Hofmann trustees endorsed the project.

Quite fortuitously, shortly before assuming her position as Frost director in January, not only did Jordana Pomeroy contract the Bruce Museum to host the first stop of Walls of Color’stravels, she also learned that the Frost owns several works — locally donated — that illustrate Hofmann’s formative period and supplement the core works in the exhibition. These paintings greet visitors entering the Frost’s Orr Pavilion galleries.

“Provincetown Docks is a classic, classic, classic American subject matter,” Pomeroy said of the Massachusetts image. “If you go to Provincetown you see all these galleries with these impressionistic paintings, but he takes it and he uses the vocabulary of the Fauves, of Matisse, whom he studied with in Paris during World War I.”

Hofmann, who was born in Germany in 1880, assimilated the precepts of Impressionism and Pointillism during his early studies. He lived from 1904 to 1914 in the artistic hothouse of Paris, where he befriended the most prominent Cubist artists. He absorbed the influence of the Surrealists and Fauves as well as the spiritual orientation of Kandinsky. Gradually, he synthesized his own conceptual framework and directed a school in Munich for 10 years. American students invited him to teach in Los Angeles in 1930. At that time, the Social Realism of the Depression was engaging with the radical influences of the various European movements. In the 1930s Hofmann established key schools in New York City and Provincetown, which he led until 1958, inspiring a generation of artists with his dynamic classroom presence, extensive writing and his exhibitions — notably in Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery, the Whitney Museum and the Venice Biennale.

An audacious experimenter, he inculcated his students with a daring attitude. In a 1950 interview with Elaine de Kooning for ARTnews, he said, “At the time of making a picture, I want not to know what I’m doing; a picture should be made with feeling, not with knowing. The possibilities of the medium must be sensed.”

Among the crucial ideas he taught and conveys in his work:

▪ Retaining the integrity of the picture plane as a surface on which paint is applied (rather than seeing it as an illusionistic window).

▪ Spontaneously liberating paint handling, incorporating irregular textures, pouring, stains and splotches.

▪ Using the “push and pull” of contrasting tonality and color to create a spatial sense, rather than the traditional Renaissance-based perspective system.

▪ Choosing color juxtapositions that interact in their own terms, rather than based on the external world.

▪ Drawing to express emotional energy states as well as to define shapes, planes and spaces.

Hofmann was already an established figure when his first mural opportunity came about. Samuel Kootz was a gallery owner with a deep commitment to promoting innovative American and European artists. Kootz viewed his gallery as a cultural laboratory, providing cross-disciplinary encounters. In 1950 he organized an exhibition called The Muralist and the Modern Architect, which paired collaborative projects among artists and architects. He introduced Hofmann to the architectural team of José Luis Sert and Paul Lester Wiener, who were working on an urban re-design for Chimbote, Peru. They requested that Hofmann design a large mosaic mural for a bell tower-like structure and pavements for a plaza walkway. “Hofmann was 70 years old. All of a sudden he was faced with this slab, which presented a new challenge,” said Silver.

Hofmann immersed himself, creating not only numerous sketches but the series of large-scale paintings that make up the fulcrum of the exhibition and show brilliantly in the high-ceilinged gallery. While he initially referenced landscape, indigenous fabric and Aztec motifs, Hofmann determined to create authentic, intuitive, abstract designs, rather than culturally inspired pictorial images. His designs, arranged in tiers, continued the experimental approach he was already engaged in, emphasizing large planes of vibrant color that would become increasingly dominant in his work. Silver argues that, “It’s really because of the murals that Hofmann finds himself being such an extraordinary artist for the last decade of his life.”

The Chimbote design’s linework is energetic, with striking counterpoints of direction, angularity, wiggles and soft arcs. The collaboration, which also included the team’s architectural models for the city, was the most highly praised element in the Kootz exhibition. Unfortunately, the project was never realized. A political shakeup —one of many in post-war South America — led to its abandonment.

In the richly illustrated book that accompanies the exhibition, Silver quotes Fernand Leger, the French artist who designed numerous murals: “The mosaics of Byzantium, like the first works of Giotto which they directly inspired, do not use the third dimension. And thus, instead of destroying the wall, they respect it.” This aligns perfectly with Hofmann’s orientation. Large fields of color, enlivened by contrasted “Pointillist” color mixing, combine with textural effects to enhance architectural surfaces. The permanence of glass mosaics is the clincher.

Two years after hosting the Muralist exhibition, Kootz brokered a deal with architect William Lescaze and developers William Kaufman and Jack Weiler to incorporate a Hofmann mural in their new office building on Third Avenue. Their shared goal was to vitalize the lobby with the colorful, vibrant energy of Manhattan. Hofmann designed a four-sided mosaic for the elevator enclosure. In the Frost exhibition, oil sketch designs plus photographs of the brilliant pristine mosaics in situ demonstrate Hofmann’s dynamic combination of yellow, red, green and blue rectilinear color blocks with serpentine meanders and squiggles of calligraphic linework. While Hofmann didn’t actually set the tesserae into cement on the wall, the highly regarded Foscato mosaic company in Queens fabricated them under the artist’s supervision.

According to Silver, many murals were being designed and executed during the 1950s — and did provide prestige and market value to the buildings they adorned, but, “The New York art world emphasized easel painting, because that’s what you can sell.” Hofmann’s contributions remained hidden in plain sight. Two years later, his third mural was commissioned. World War II had generated a great need for new schools — the baby boom was under way. The New York School of Printing was part of an International Style public school campus intended to support the burgeoning printing industry. The architecture firm Kelly & Gruzen incorporated an 11-1/2- by 64-foot blank wall in the auditorium-gymanasium building for a Hofmann mosaic mural. Gruzen already owned works by Hofmann and contacted the artist through Kootz. Hofmann’s initially geometric design evolved to incorporate increasingly dynamic biomorphic elements that alternate with the geometry. The mosaic interpretation is masterful; the catalog shows a photographic detail of a central element in which “brush strokes” are reproduced in a trompe-l’oeil style amid a broad range of intermixed blue tones. Better yet, the exhibition includes an actual mosaic maquette that physically embodies the rich materiality of the finished work.

The exhibition concludes with the work that initiated Silver’s project: the slab paintings. He and other scholars speculate that rectangular color blocks — essential components of a mosaic — become an increasingly prominent feature of Hofmann’s paintings. They anchor his compositions amid the dance of agitated brushstrokes, textures and stains. They also echo Hofmann’s respect for the fundamental rectilinearity of the canvas or paper support. Moreover, his mural design process had entailed collage-like mock-ups of large painted sheets of solid color. Echoes of Matisse.

For Pomeroy, the exhibition’s inspirational value to Miami architects and students is key. “We have a really strong architecture program here at FIU, so it goes without saying that they’ll be coming here to see it.” The current development boom and explosion of artistic enterprise create a compelling potential for collaboration. “It’s about that spirit that permeated the mid-20th century — of artists and architects, developers, sculptors and dealers all thinking about the bigger picture. What can we do today — especially in Miami — that would really imitate and model ourselves on these kinds of relationships?”

Five additional exhibitions at the Frost will amply reward a day-long visit. In particular, Ramón Espantaleón’s mosaic-like “topographic map” of New York City, overlaid with a painted version of Michelangelo’s Temptation and Expulsion, should resonate with Hofmann’s bold experimentation.