Lowe Art Museum director Jill Deupi and curator/portrait collector Robert Flynn Johnson discuss the exhibitions.

BY GEORGE FISHMAN

A year ago, when Jill Deupi was just four months into her tenure as director of the Lowe Art Museum, she introduced a pair of exhibitions on African and Haitian art with this thought: “The power of art is to remind us what it is to be human.” Currently, the Lowe is hosting very different exhibitions that reflect that ethos. They also reveal Deupi’s deft balancing of old and new, including a collaboration with the Bass Museum, which is closed for renovations until fall.

While previous shows were organized and scheduled by her predecessor, Brian Dursum, those on view now come from Deupi’s own initiative. In a city best known for its contemporary exhibitions and street art, the Lowe has bragging rights to an encyclopedic collection of more than 19,000 objects encompassing 5,000 years of artistic activity. “My goal is to remind people of these remarkable holdings we have,” Deupi said in a recent interview, “while also making them relevant.”

CONTEMPLATING CHARACTER

Accessibility is key to relevance, and few subjects reach out and touch as effectively as portraits. In this day of ubiquitous and often mindless “selfies,” the 132 drawings and oil sketches that constitute Contemplating Character, sensitively organized and documented by curator-collector Robert Flynn Johnson, provide a variously tender, brutal, sexy, haughty, haggard and comedic set of characters. “I was looking for a show that walks that fine line between being serious, being fairly comprehensive, but also having a wow factor,” Deupi said. Comprehensiveness derives from the show’s 250-year span, from the Napoleonic era to Travis Collinson’s 2010 Self Portrait.

The show does include portraits in which the stiff dignity or fragile beauty of the sitter is showcased. But more often, it’s an intense psychological state or circumstance of extremes that captured the artist’s attention — like the rugged endurance expressed in the knobbly visage of Lucian Freud’s elderly mother. “When you’re looking at the images of people from all walks of life — the great and the good and the very humble and ordinary who are often forgotten — you’re reminded that we all go through this very difficult thing called life,” Deupi said. That difficulty is reflected in work by the highly accomplished 19th century painter, César Ducornet, born with no arms.

Among the show’s most notable objects is a tiny watercolor of an eye, painted on ivory and surrounded by amethysts, that served as a secret keepsake for a clandestine lover. Its talented creator is unknown. Remarkable in a very different way is Edouard Vuillard’s 1897 wash drawing that appears entirely abstract, or vaguely floral, until you realize it depicts the backs of three women’s hats at the opera. Every viewer of this unique exhibition is sure to find numerous images that will long linger in memory.

Selected from the personal collection of Johnson, a San Francisco-based curator and author, these often quirky works reflect the unique taste and character of the collector. Recognizing himself as a “people person,” Johnson said he realized he was more interested “in man himself” than in landscape, still life or “the cool abstraction that man makes.”

In his professional role as an adviser to museums on acquisitions in all genres, Johnson focused his own more limited budget on portraiture. This bias proved beneficial; as a dealer advised him early on, “If it wasn’t a famous person or a really pretty girl, these works of art were less expensive … I found that it was a wonderful potential area to collect in,” he said in a phone interview. Because the best known artists were not financially accessible, Johnson consistently favored the finest examples of highly skilled and imaginative artists rather than “tiny scribbles” by the most famous — old or modern.

This is not to say viewers won’t find works by household names, among them William Merritt Chase, Edouard Vuillard, Edgar Degas, George Bellows, Edward Burne-Jones, Pierre Bonnard, Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Freud, Alfred Hitchcock, Robert Crumb. In some cases, the subject is better known than the artist, as with the exquisitely detailed bust of George Washington, only 5/8-inch tall, drawn by an anonymous Frenchman in about 1895.

Some works are striking for the intensity or tenderness of emotion; others for their uniqueness of composition, detail, format, historical context. Wisely, Johnson arranged the works into a logical set of seven categories and collaborated with Deupi in configuring the installation according to these “chapters” (self-portrait, family, fame, drama, etc.) rather than by date. These groupings stimulate reflection on the passage of time, personal drama, character, notions of beauty and artistic style. A catalog is in production; meanwhile, Johnson’s succinct wall texts provide vital information in an accessible style.

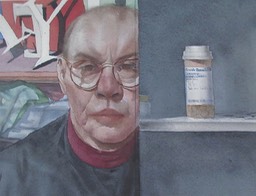

At Deupi’s suggestion, the show includes two very distinctive works, one hung above the other. One is a 1943 delicate black chalk self portrait by Dora Maar — painter, photographer and one-time Picasso muse — that the artist cut vertically in half with a razor blade. Above it hangs DeWitt Hardy’s sensitive self portrait, his reflection split by an open mirrored medicine cabinet containing a pill bottle. Hardy is diabetic, and this spare, familiar view quietly evokes our common mortality. Johnson calls them selfies, “except they’re not self portraits where you click and forget … These are selfies where the artists have used their imagination or stared into the mirror and really dug into who they themselves are.”

LILIANE TOMASKO

“The challenge of painting is to clear away the surface in order to unveil the unseen.” Colombian painter Carlos Salas has said about his own work, currently on exhibit at MOCA in North Miami. It’s an apt introduction to Liliane Tomasko’s exhibition, Mother-Matrix-Matter, as well.

Many of Tomasko’s darkly glowing paintings share a soft focus, somber muted tonality and enigmatic subjects. Most are piles of blankets, though you may not recognize them as such before you read the accompanying text. Tomasko, who studied sculpture in London, has developed a hybrid technique that results in paintings somewhere between representation and abstraction, ambiguously suggesting surface, space and mass. Images like Hush and Delirious bear the fuzzy contours of a fading dream — or of nappy, rumpled blankets viewed from inches away. Other works show greater interest in linear patterning, texture and the tangible flow of variously textured paint. Tomasko doesn’t consider her paintings to be abstract, but as Deupi says, “She certainly looks at the world with abstract eyes.”

Her method is no secret; during a process of stacking and re-stacking folded blankets and coverlets, she takes small-format Polaroid photos from various distances, which serve as source material or “subject.” Her paintings and drawings emanate the luminosity found in works by such disparate artists as Mark Rothko, Bonnard and the candle-lit interiors of Baroque artist Georges de la Tour.

Her adoption of the domestic world as a theme is not only visual. The bed is where most of us were conceived; where most people were once birthed and where many of us will die. It’s also the domain where children (Tomasko is a relatively new mother) burrow under blankets to play hide-and-seek and where adults escape to repose, mourn or relax with a book. “It’s a very, very loaded locale,” Deupi summarized. Tomasko quietly bestows it with mystery and grandeur.

GOOD NEIGHBORS

When another Miami collecting institution, the Bass Museum, closed its doors last spring for extensive renovation, director Silvia Karman Cubiñá reached out to Deupi with the suggestion they collaborate. The resulting exhibition, hosted at the Lowe, highlights the Bass’ northern European holdings that complement the Lowe’s Kress collection of Italian Renaissance and Baroque works.

One of the most compelling works here is Gerard Segher’s Christ and the Penitents, in which Christ, surrounded by a cast of emotionally fraught figures, reveals the wound on his chest and gestures to the viewer. The painting’s dramatic tension embodies its baroque style. It would be unfairly limiting to call this a “best-of” show, but each woodcut, altarpiece, tapestry and painting is a marvel of its genre and period.

Nearby, Rubens’ 1615 theatrical staging of the biblical story of Lot and His Family Fleeing Sodom conveys a foreboding tone. Lot’s avaricious daughters are dressed in the gorgeously rendered silks and satins for which the artist’s studio was famed, but we know from the gathering storm clouds and the symbolic column behind the patriarch and his wife that tragedy will soon strike.

Lot’s family lacks the legendary fleshiness of Rubens’ women. But voluptuousness is provocatively displayed in in a 21st century reworking of the Dutchman’s portrait of his second wife, Helena Fourment. New York artist Kathleen Gilje has rendered his wife, 34 years his junior, with remarkable faithfulness to the original. She’s fresh from the bath and revealingly draped in fur, but in this rendition, she’s creepily gripped by the hands of an invisible “dirty old man.”

Albrecht Dürer’s Sampson Fighting the Lion from 1497-98 reveals the artist’s transition from Gothic to Renaissance style in illustrating this biblical story. Even viewers unfamiliar with the religious iconography will admire the dizzyingly complex linework Dürer achieved to create perspective, with convincing stops in fur, flesh, foliage, stone, water and clouds.

Recalling a conversation with retired University of Miami president Donna Shalala, Deupi said, “Her very simple mandate to me when I came in was to put the Lowe back on the map.” The museum’s current offerings, skillfully juxtaposing “canonical” with contemporary work, are doing just that.

Listen to audio: bitly.com/LoweCommentaries