Inside Looking Out, Outside Looking In

by George Fishman

What distinguishes art that’s “inside” today’s mainstream from that which remains “outside?”

Which artists were self-taught, and which were academically trained?

And in what roles do we find artists of color?

These questions can be difficult to answer, except on the basis of where you’re seeing the art.

These are among the topics of investigation by Thomas J. Lax in “When the Stars Begin to Fall; Imagination and the American South,” the recently mounted traveling exhibit at NSU Museum of Art in Fort Lauderdale.

Formerly assistant curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, where the show was organized, Lax was recently appointed associate curator of media and performance at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

His exhibition, richly textured and intriguing, plays well into the interests of Bonnie Clearwater, NSU’s director.

“I’ve been fascinated with the issues explored in this exhibition throughout my career,” Clearwater said.

She explored the insider-outsider art conundrum in the first exhibition she initiated at NSU, featuring young Brooklyn-based black performance/video artist Zachary Fabri, who was born in Miami and previously exhibited at the Studio Museum. Fabri explores cultural ideologies and questions issues of “us and them” in his work, staging guerrilla performances in New York museums — among other interventions.

The Studio Museum, established in 1968, is, in Lax’s words, “a hub for both black artists, living locally, throughout the United States and throughout the world — and for the many people who enjoy their work and want to engage with it critically.” It’s a place to discover how central black culture is to American culture and to the global art scene. And it’s a venue in which Lax developed his curatorial orientation.

“For me, the role of the curator is the role of the advocate first and foremost,” he said in a phone interview. Paradoxically, he said, in presenting artists who work in obscurity, he has found that some need shielding from the machinations of the commercial art world.

Many of the 36 artists in the exhibit are at the center of the mainstream art world and have academic backgrounds (Deborah Grant, David Hammons, Kerry James Marshall, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, Lauren Kelley, Rodney McMillian, Jacolby Satterwhite, Rudy Shepherd, Xaviera Simmons are likely the most familiar). Others work — or worked — in isolation, and Lax’s idea was to bring them together through the theme of self-taught. Lax said this exhibition “wasn’t meant to chart a history of time and place. It’s about thinking through categories.”

In doing so, he has created a fascinating and fantasy-rich exhibition, whose name derives from the chorus of an African-American spiritual.

The insider-outsider question isn’t new, but it is certainly trending and relevant. While Lax and his colleague Elvis Fuentes worked at the Studio Museum, Fuentes was developing “Caribbean: Crossroads of the World” (shown recently at the Pérez Art Museum Miami), in which works by self-taught artists mixed it up with those of their academically trained counterparts. At the 2012 Whitney Biennial, Lax was intrigued by Robert Gober’s presentation of the Texas gulf artist/fisherman Forrest Bess’ enigmatic paintings and medically related documents. And last year’s Venice Biennale was also notable for the intermingling of mainstream artists and “outsiders.”

Interested in this phenomenon, Lax decided to create a show that framed the inquiry within the context of African-American artists and the geographic locus of the American South. “So, I kind of worked to think through who would look and give meaning to other objects in the show by their juxtaposition. It became kind of an associative process,” he said.

The show’s unpredictable counterpoints of color, similarities and contrasts of roughness and sheen, scale, realism, abstraction and widely disparate moods create an ever-shifting experience. This is underlain by a sound mix that emanates from numerous videos and from Kevin Beasley’s audio installation.

The American South remains a place of origin — real or mythical — for many blacks who migrated to northern cities while retaining stories, craft skills, recipes and other artifacts of “home.” The South also embodies the pleasures of rural life and the horror of slavery. Rodney McMillian’s six-minute video, Song for Nat, refigures the story of Nat Turner’s leadership of a slave rebellion as a Blair Witch Project-like presentation, in which the protagonist, wearing a white hazmat suit and mask and carrying an ax, eerily stalks a suburban “plantation house.”

Marie “Big Mama” Roseman, a midwife, herbalist and seamstress, late in life took her homespun needlecrafts to almost bizarre levels of elaboration, engulfing a pillow, quilt and cushions with multi-colored wrapped yarn, sequins, ribbon, a large plastic leaf, bunched fabrics and wild stitchery.

Kara Walker is known for “mining the horrors of American history through her own fantasy and projection and irony, but she is also somebody who’s interested in 19th-century American self-taught painting,” Lax said. Her jerky, “hand-made” video, 8 Possible Beginnings, or the Creation of African-America; a Moving Picture by Kara E. Walker, suggests a faux naive sensibility that only amplifies the misogynistic narrative. It shares a room with Kerry James Marshall’s darkly hulking Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein. Both artists are academically trained, with deep historical knowledge, but here they mask their “chops” to plumb and excoriate myths and stereotypes. Lax refers to this as “invoking an avatar or veiled projection of themselves.”

Such ambiguity is not exclusive here, as contemporary art revels in breaking with convention, but Lax’s research has revealed that institutions of power have historically been more embracing of art by black artists who were self-taught — which these artists acknowledge.

Installing the show in the NSU galleries required fine tuning. “We worked very closely to make sure that all the grammar of the show — how things look next to one another and how they were paced and placed — would be specific to their space and make sense to their audiences,” Lax said.

The inclusion of Purvis Young’s vibrant and iconic Untitled Book in creating the South Florida configuration of the exhibition pays homage to a highly regarded and unique South Florida figure. “I felt it was crucial to add him in Fort Lauderdale, and Thomas happily agreed,” Clearwater said. “We borrowed an early work by Purvis from the collection of César Trasobares, one of the artists in our current exhibition of first-generation Cuban-exile artists. This loan created a wonderful bridge between the two shows.”

At the base of the staircase, near the Miami Generation Revisited show entry, Xaviera Simmons’ boldly declamatory street sign-inspired text both invites and warns of what lies ahead in the second-floor gallery installation.

Self-taught artists who were incarcerated, diagnosed with mental illness or had visions or religious callings form the most familiar category in Lax’s organizational scheme. Many of these artists use improvised materials: scrap paper; ballpoint pens; construction debris; office forms; bottle caps; candles; markers.

Henry Ray Clark’s On Our Planet Name Yahoo We Are Called Destiny Childs We Sing and Dance to We do Know One Thing For Sure We Will Never Separate Are Be Apart readily fits the visionary designation. It features elaborate concentric decorative borders that surround a fantastical three-headed, three-breasted creature. In fact, the artist began drawing while incarcerated, and his dense compositions on manila envelopes freed him to enter and share an intergalactic imaginary world. Invented languages, spiritual symbols and alternative cosmologies characterize numerous works in this genre — some of whose creators began their art careers following spiritual visitations.

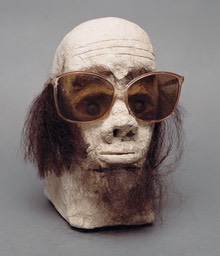

Bessie Harvey’s Black House of Revelation and Thousand Tongues also represent the revelatory stream of invention. They spring forth in riotously tangled carved, painted and assembled sculptures that radiate energy. James “Son” Thomas’ molded clay portrait heads, accessorized with wigs and sunglasses, are hauntingly arresting, displayed atop a wall.

Some artists have devised their own exhibition and performance spaces, adopting curatorial roles; these comprise Lax’s second grouping. Theaster Gates’ multidisciplinary background includes both ceramics and church performance, and his practice also encompasses urban revitalization. He organized the socially engaged Soul Manufacturing Company while in residence at Miami’s Locust Projects in 2012 and was recently awarded a $3.5 million Knight Foundation grant. Billy Sings Amazing Gracedocuments one of his collaborations with non-artists, creating a narrative between his trajectory and theirs in performance venues he has created.

Noah Purifoy’s “Outdoor Desert Art Museum in the Mojave Desert” is another artist-made exhibition venue. Documented by photographs, it’s a mammoth installation of idiosyncratic structures, roughly assembled from construction materials and detritus. They reference modernist sculpture, Dadaist sensibilities, diverse building types and specific social events. Minimalist, they’re not.

Beverly Buchanan’s clusters of sculptures share elements of Purifoy’s aesthetic, but on a more personal scale.

Other artists have adopted modes of working that used to fall outside the standard visual arts categories of what a museum would exhibit, but now align with the emerging disciplines of multimedia, video and interdisciplinary work. Not coincidentally, this is the area of Lax’s special interest and expertise. It forms his third organizational division.

Courtesy the Artists, a collaborative, presents complex, multimedia works often based on political/historical events. One series includes drawings of videos of invited artists’ interpretations of the traditional song Black is the Color (Of My True Love’s Hair), which bears layers of historical association, including ties to the civil-rights movement.

Ralph Lemon creates entrancing interpretations of the southern Uncle Remus folk tales through his photography of costumed enactments, staged in his collaborators’ home. The mundane settings amplify an unsettling ambience, reinforcing the notion of the South as a world apart, where anything might occur. Extensive wall texts provide specific biographical information about artists’ personal iconographies and broader thematic context without constraining the immediate experience of the artworks, whose rigor, potency and inspirational origins retain their mystery.

When the Stars Begin to Fall doesn’t try to definitively answer the questions it poses, but it makes them absorbing and vivid.

IF YOU GO

What: ‘When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South,’

When: Through Oct. 12

Where: NSU Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale; One E. Las Olas Blvd., Fort Lauderdale

Info: 954.525.5500; www.moafl.org/

Also

Lectures, films, and performances for adults and youth complement the exhibition.

▪ On Sept. 27, Professor Andrea Shaw speaks on magic and rebellion in the Black Diaspora.

▪ Edouard Duval-Carrie will curate a history of Haitian photography next spring.

▪ Listen to Thomas Lax (via Skype) bitly.com/ThomasLax