New exhibits at Wolfsonian-FIU show museum’s knack for staying modern

BY GEORGE FISHMAN SPECIAL TO THE MIAMI HERALD

Audio

Hear Cathy Leff on the Power of Design symposium. bitly.com/CathyLeffPOD

Hear Matthew Abess on the Bosch portrait. bitly.com/MatthewAbessBoschPortrait

How is a museum to compete when “Googling” provides access to almost any cultural artifact past or present? Baroque portraits by Franz Messerschmidt, Marvel comic heroes, videos of yesterday’s music festival, design drawings for both missile launchers and merry-go-rounds — all can be viewed with a few clicks. What will inspire folks to drive, park and pay to peruse real objects when their virtual counterparts are mere keystrokes away?

The Wolfsonian-FIU in Miami Beach is meeting the challenge — as are other institutions — by making their presentations ever more relevant and compelling. How? By initiating projects that link the historical and contemporary, raising provocative questions and thereby amplifying the appeal of those selections.

Current exhibitions Art and Design in the Modern Age and The Birth of Rome grapple with notions of mankind’s perfectibility through technology. But equally present is its capacity to debase. Both are embodied in the uncanny white Bust of a Doctorsculpture, a contemporary portrait of “pill doctor” Anthony Bosch eerily lying on its side within the lantern-like Bridge Tender’s House just outside the museum entrance.

The Bridge Tender House is one of two hexagonal stainless-steel structures built to shelter the operators of the 27th Avenue Miami River drawbridge. When these were replaced in the 1980s, one was given to the collection. Since 2008, selected artists have been commissioned to use it as a venue for provocative images and messages. Recently retired director Cathy Leff characterizes the Bridge Tender House project as “a way for us to invite artists in to look at the collection and see how it relates to their work . . . and give a contemporary voice to our collection.”

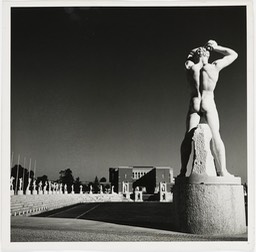

Miami-based Gideon Barnett is the latest, and his work leads visitors up to the sixth floor to maquettes of Mussolini’s commissioned statues of athletes, prefigured in ancient Rome. Through his utopian project, Mussolini sought to create an ideal “New Man” of zealous action. Like other utopian visions led by dictators, the Fascist project failed spectacularly.

This is the type of investigation that the Wolfsonian so effectively articulates. The Rebirth of Rome is a series of exhibitions that uses a wide variety of genres to explore themes of Italianness, political identity and a progressive, self-aggrandizing spirit during the Fascist era. Barnett’s portrait of Bosch brings a face from recent headlines to this theme.

‘IDEAL’ ATHLETES

Curator Matthew Abess sets the contemporary context of Bosch: “So here you have a figure who, in many ways, extended this narrative of human and machine cohabitation, of the ongoing manipulation — by human will — of the natural world and its natural order. In this case [it’s] through the genetic enhancement of major athletes.

“So the artist Gideon Barnett, whose practice is primarily in photography, was invited to create an installation for the Bridge Tender House that engaged both with its own context as well as our temporary exhibitions collectively titled Rebirth of Rome.”

That engagement goes deep. The masterful maquettes (part of the larger Rebirth of Rome exhibition series) evoke the 60 monumental marble figures that surround the Foro Mussolini (now Foro Italico) in Rome. This sports and education complex, designed under the Fascist dictator’s direction, was part of a grand scheme to modernize the city and unite the 50-year-old Italian nation, “branding” it with the aura of Imperial Rome. These idealized athletic bodies epitomized this inflamed vision of strength and vitality.

Barnett takes on this theme not by portraying a great contemporary athlete but instead a disgraced celebrity. As Abess explains, “He may be best known by those here in South Florida and by those interested in professional sports as the founder and director of the Biogenesis clinic in Coral Gables, which is now known to be responsible for many of the doping scandals that have rocked the major figures of major-league baseball. So, already his entire practice was an extension, according to the technologies of our own time, of perfecting, genetically enhancing.”

Here was technology directed to create “ideal” athletes by co-opting nature in a morally corrupt enterprise. So, to produce a portrait of the steroid-dispensing Bosch, Barnett extended his own photography practice into three dimensions, using another contemporary technology. This began with the capture and compositing of images from the Internet to form a 3-D model and then realizing it by means of 3-D printing in plaster.

Art and Design in the Modern Age has distinctive examples of conflicting responses to modernism. They Swapped Horses for Steel Steeds is the slogan on a Russian Imperial Porcelain Factory plate from 1928. Post-revolutionary leaders optimistically forecast that mass industrialization would quickly lead to an ideal society. In the lower half, the design depicts the bad old days (shown in black and white) when men struggled to cultivate their fields with horse-drawn plows. Above, in glowing color, tractors have tamed the rolling hills.

“Now we can look back at this and see it was a completely failed endeavor,” Abess says. “The attempt to industrialize so rapidly, concurrent with the collectivization of farms led to a disaster in the area of food production, mass famine, mass starvation. And so here you have a pretty little plate that, in fact, sought to carry out some fairly serious persuasion.”

When New Yorker Virginia Berresford painted The City in 1936, she expressed none of the optimism of her near-contemporary Russian designer. Instead of a Promethean image of man as maker and builder, she presents a beleaguered man and a defoliated tree. The metropolis glows as a pale chimera in the background, but the dominant scene carries a bleak message. Abess characterized her portrayal as “the backside of the modern world.”

Just as effective in conveying a very different sentiment is a silver-skinned tower, thrusting skyward. It is actually a scale, such as those in a doctor’s office or supermarket, but it embodies the buoyancy of its designer. Even if not intended as propaganda, its subliminal message is strong. Once again, an object is never just an object.

Lively and pertinent presentations of the Wolfsonian’s collection are enhanced by film screenings, lectures and activities like the recent Power of Design symposium. This was the first annual “think fair,” consisting of discussions, exhibitions, humor and prizes. “Complaint” was the theme and point of entry, designed to stimulate real world problem-solving. According to Leff, “more of a solutions think tank than a gripe fest.”

Urbanism, globalization, body image, hero worship — all are as current now as when the Industrial Revolution first provoked promotion and protest. By maintaining the relevance of their collections through active engagement with hot topics, institutions like the Wolfsonian successfully draw audiences away from passive engagement with digital screens and through the museum doors.

Read more here.