MOSAIC PORTRAITURE – INTRODUCTION

George Fishman

What more personal and essential vehicle for artistic expression than the portrait? The attempt first to observe, then to characterize ourselves, our fellows - especially those whom we love and revere - has been one of visual artists' earliest and most enduring endeavors. The desire to fix that which is ephemeral flows naturally from recognizing our mortality and questioning what lies beyond the tangible. Sculptors have carved stone and wood, hammered metal, modeled clay and wax, trying to re-create a three-dimensional likeness. Other artists have directed their efforts to two-dimensional surfaces, using both humble and precious materials.

The transcendence is truly amazing to me every time I go to a museum and I see how somebody figured another way to rub colored dirt on a flat surface and make space where there is no space or make you think of a life experience. - Chuck Close

The most accomplished artists do more than mirror their subject's appearance; they convey motion, mood, character, essence, ideals, presence. They tell stories and offer both carnal temptations and moral principles - sometimes simultaneously. They create casual, naturalistic portraits as well as flamboyant masks. Their styles run a rich gamut from flat and graphic to meaty to stony to ethereal.

Among the many modalities chosen for portraiture is mosaic, a distinctive and ancient medium, but one that serves the same core potential to carry the intentions and skills of its practitioners as do, for instance, graphite, paint and photography. That said, mosaic has its own unique range of characteristics to explore.

One cloud has hovered over mosaic: It has been co-opted to translate designs from other mediums into a permanent form, instead of standing as an art form in its own right. As a result, some have relegated it to a subservient status.

Emblematic are the mosaics of the Vatican, rendered with meticulous skill from oil paintings by Raphael and others. During the 20th century, artists renowned for work in other mediums, among them Chagall, Leger, Siquieres, Rivera, Bearden, Gilliam, Haas, Graves, Paladino, Stella, Held, Graves, Lewitt, Lawrence, Beal, Anuskiewicz, were commissioned to design works that were executed by others for airports and other public spaces around the world.

Even in much earlier times, mosaic studios usually consisted of a hierarchy of specialist practitioners, headed by the pictor imaginarus, the lead designer who drew or painted the images that would then be transferred to a wall or floor for others to execute in mosaic. This team approach (paralleled in painting and sculpture studios) has practical advantages, especially for monumental work.

Much as skilled bronze casting or lithography technicians apply their skills to the production of sculptures and prints based on prototypes (wax models, drawings, paintings, etc) that are brought into the workshop, many mosaicists pursue a comparable centuries-old practice: They interpret the designs of other artists in glass and stone. Some also design their own work; others not. Moreover, mosaic is an architectural surfacing material and a medium for industrial and craft use: tabletops, trays, birdbaths, etc. These perfectly valid applications of the medium have had the unfortunate effects of disguising and undervaluing the fine art expressions done with the same materials and also called “mosaics.”

The purpose here is to present and contextualize contemporary fine art mosaics. This book, the first of a series, utilizes the theme of portraiture; forthcoming books will explore other subjects, each time highlighting some of today's most accomplished practitioners of this time-honored artistic medium.

The artists presented within this book both design and execute their work. As Lucio Orsoni, celebrated mosaicist and head of the historic smalti production atelier in Venice has long maintained, one must "think in mosaic" to create great work - not translate designs from other mediums. This is a core belief among many of the artists here and gives immediacy to their work.

Ilana Shafir writes: The spontaneous approach to mosaic making involves moment-to moment assessments of what would make a "right" piece. The "right" piece is not a preconceived or pre-visualized aspect of the mosaic. Rather it is the result of a decision that is made at the spur of a moment during the creative process of searching. It leads to unexpected and surprising results.

But this is not everyone's path into a portrait.

Carol Shelkin says: I take many photographs of my subject, paint pictures and build value drawings before I find the face I want to develop into a flickering glass mosaic. Painting is the beginning for me and an exercise and the foundation before I begin to develop the portrait with glass.

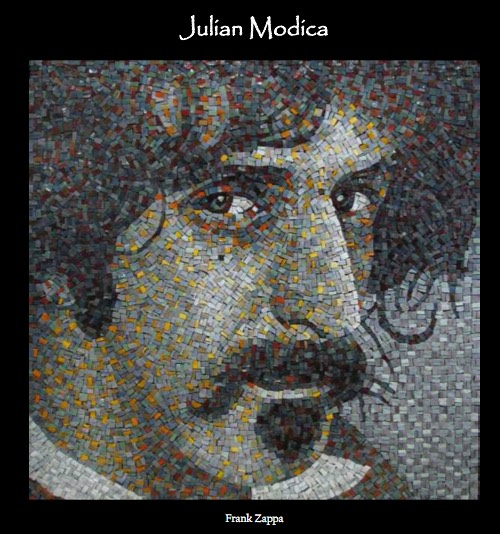

Just as music is made of sounds AND silences, mosaicists exploit the spaces BETWEEN the chips of hard stuff to make their magic. Julian Modica brilliantly exploits the broad faces and narrow sides of his smalti to create the varying width of interstices that mysteriously evoke his “Marilyn. “

Mosaicists not only use their materials to "paint" in glass and stone, but also exploit other fundamentals of the mosaic process, as we shall see.